Introduction

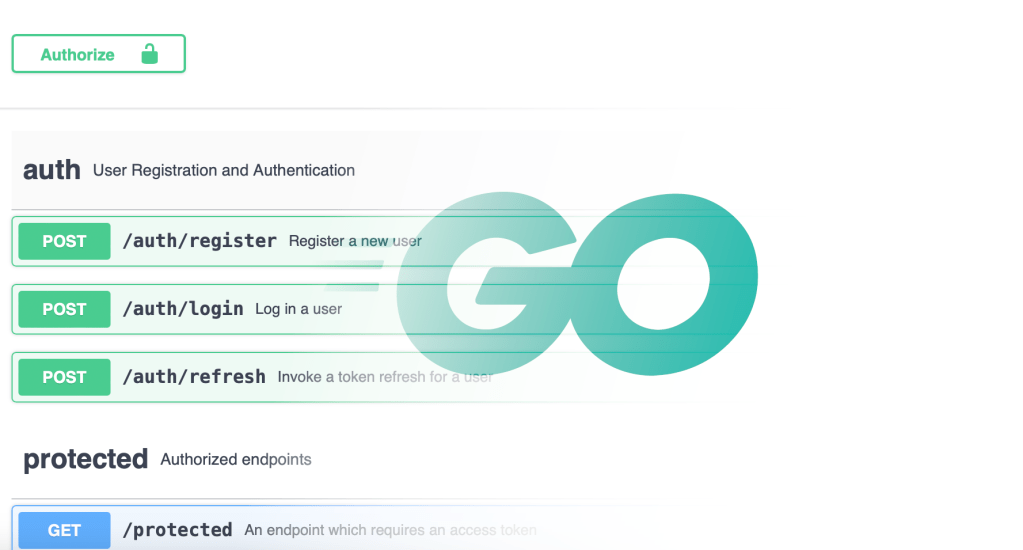

In part 1 of this series, I introduced a Golang template project I’ve produced to simplify creating web services with credential-based authentication and authorization. If you haven’t yet read that article, it provides context for the material ahead.

In this article, I discuss the database integration in the template. I’ll present MongoDB as my NoSQL database backend solution with brief reference to differences when using a relational database like Postgres or MySQL.

Let’s continue.

The Provider Interface

The auth module of the template exposes a Provider interface which is used to persist user credential and token information. This approach enables sharing existing database connections to store auth-related data. The auth module is database agnostic. It’s designed to enable using a Postgres SQL provider on one project and a MongoDB NoSQL provider on another, for example.

The API is fairly compact, defining a few types and some errors, along with the interface itself:

type Provider interface {

GetUser(email string) (*UserInfo, error)

GetUserByID(userID UserID) (*UserInfo, error)

InsertUser(email string, hashedPassword string) error

DeleteRefreshToken(tokenID TokenID) (*RefreshTokenInfo, error)

GetRefreshToken(tokenID TokenID) (*RefreshTokenInfo, error)

InsertRefreshToken(userID UserID) (TokenID, error)

UpdateRefreshToken(tokenInfo RefreshTokenInfo) (error)

}In order to utilize any of the auth route handlers, an implementation of this Provider interface must be passed in. We’ll look at the implementation details after we get MongoDB hooked up.

Connecting to MongoDB

The template utilizes MongoDB for database requirements. I prefer working with MongoDB over Couchbase, another popular NoSQL database, which I have experimented with in reasonable depth. On the relational database side, I previously implemented similar providers using both Postgres and MySQL.

In utilizing Mongo and NoSQL for this example, I avoid considerable overhead related to schema management. Initializing and evolving a relational database schema adds a considerable amount of integration overhead. If your service is better suited to a relational database, you will already be managing this overhead and the minimal additional schema needed by the auth module will be a small burden to manage.

The database connection logic in the template is boilerplate derived from the MongoDB driver docs. I’ve slightly extended the logic to use an environment variable (DB_URL) to provide a configurable server location. I also added a simple retry mechanism to make connecting a bit more robust on cold starts of the service. In testing scenarios, I typically spin up a DB server simultaneously with the web service. This simple web service will win the startup race every time, so the retry accommodates the slower DB startup.

Provider Implementation

The provider interface is implemented using our MongoDB connection. First, we define document types for the User and Token using Mongo bson identifiers and data types. The interface requires that the User contain an identifier, email, and hashed password:

type userDoc struct {

ID primitive.ObjectID `bson:"_id"`

Email string `bson:"email"`

HashedPassword string `bson:"hashed_password"`

}Note that a more complex service could add fields to this database document for its own purposes. Perhaps the service wants to show a name or an avatar for the user. These fields might be managed by separate /users routes keyed by user ID.

The user document is created by the InsertUser interface method. First we ensure email uniqueness by trying to find an existing document with the same email in the users database collection.

var existingUser userDoc

collection := m.database.Collection("users")

err := collection.FindOne(

context.TODO(),

bson.D{{Key: "email", Value: email}})

.Decode(&existingUser)

if err == nil {

slog.Warn("attempt to register existing user",

slog.String("email", email))

return auth.DuplicateUserError{}

}

if err != mongo.ErrNoDocuments {

slog.Error("error fetching user record",

slog.String("email", email),

slog.String("error", err.Error()))

return err

}Finding none, we will hash the provided password and insert the resulting document.

hashedPassword, err := bcrypt.GenerateFromPassword(

[]byte(password), bcrypt.DefaultCost)

if err != nil {

slog.Error("failure hashing password",

slog.String("error", err.Error()))

return err

}

user := &userDoc{

ID: primitive.NewObjectID(),

Email: email,

HashedPassword: base64.StdEncoding.EncodeToString(hashedPassword),

}

_, err = collection.InsertOne(context.TODO(), user)

if err != nil {

slog.Error("error inserting user doc",

slog.String("email", email),

slog.String("error", err.Error()))

return err

}In retrospect, it would be an improvement to hash passwords in the auth module instead of having to repeat this code in every integration.

The remaining code in authprovider.go implements the User retrieval and Refresh Token persistence methods on the interface. These methods are intentionally kept simple with the majority of the business logic implemented in the auth module itself.

For example, the logic for chaining and invalidating refresh tokens is all contained in the auth module. The methods on the provider interface are constrained to database CRUD operations. While it might be possible to perform more efficient chain invalidation by using built-in database capabilities, the reality is that these are not high volume events in practice, so the additional complexity would be unlikely to provide value.

I won’t do a step-by-step description of each method here, but feel free to add questions in the comments.

Summary

I hope this was a useful demonstration of how to use a module interface in golang to abstract database access from the module’s implementation. One side benefit of such an approach is the ease of unit testing your module code by mocking the provider interface. I plan to write another article describing the details of the auth module implementation and testing. Stay tuned for that in the near future.

If you found this useful, please let me know by leaving a comment below. I’d love your feedback!

Be well.

Leave a comment